Last December, Eleanor Rees commented on Facebook that her poetry collection Blood Child (Liverpool University Press, 2015) hadn’t had any reviews. This is the frustrating part of writing – you can work harder than you’ve ever worked on a project, manage somehow to get it accepted by a great publisher, work yourself into a frenzy on the publicity racket, and then nobody bothers to review it.

I know Elly well – she and I were colleagues at Glasgow University last year – and not only is she very lovely, but I know her work to be top notch. So I said I’d happily review the book. And then Ruth Stacey – another poet I know, and whose work I’ve read – asked me to review her new book as well.

But when both books plopped on my doormat, I was worried. What if I didn’t like them? I wanted to write an honest review, but what if one – or both – of them was rubbish?

![FullSizeRender[2]](https://carolynjesscooke.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/FullSizeRender2.jpg)

Blood Child is an absolutely stunning piece of work, one of the most daring poetry collections I’ve read in a long time. I do not understand why it has been overlooked for review. I can’t fathom why it hasn’t made it on to one of the bigger poetry prize lists.

The richness and depth of these poems – some of them 10 pages long – the experimentation with ancient poetic forms, and the soundscapes discovered in estuaries, cities and coastlines suggests a poet who is highly attuned to the voices of place.

‘An underground stream speaks in swollen rushes.’

(‘A Burial of Sight’)

Those voices include artists, poets, and musicians whose words seem to persist within the landscapes depicted in ‘Blue Black’, for instance, which calls upon Medieval poets and an account of The Battle of Brunanburh as strata:

‘On the mulch, blood stains

into leaves; a man’s body in the shadows

slashed hard, slumps into bone in seconds.’

The poem takes a gull’s view of the land, following the line of the river, zooming in on new-builds, marshlands, gables, car parks, shorelines and inhabitants. It meanders across the pages, riverlike, but is never without a sense of control.

Rees’ poems are markedly in conversation with each other (I can’t help but feel that the ‘gulls on the bow’ in ‘Tide’ are re-encountered in ‘Arne’s Progress’, and again in ‘Blue Black’; likewise, the closing image of the book, that of children running to their mother, seem to hark back to the figures of the title poem. Each of the poems follow passageways, tramlines, paths that fold back on themselves, voicelines – as though the collection itself is a kind of map of the sounds, textures smells of memory and imagination. The landscapes in the collection are imagined in terms of their layers, the lost paths, the absent coterminous with the present. Place is made up of sediments of the living and dead, words sung and written down, mutability in all its guises.

![FullSizeRender[3]](https://carolynjesscooke.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/FullSizeRender3.jpg)

I think what I enjoyed most about this collection was that I never knew what to expect. There is a restless energy throughout, a desire to explore and experiment (particularly with the long poem) that made for riveting reading. These aren’t poems that can easily be categorised in terms of what they’re about, and they only tell stories insofar as acknowledging the threads that bind each narrative together, rendering it (and us) inseparable across time and space. I felt like I kept wanting to return to the book, as though the poems would reveal something more with each read – and that’s the best kind of poetry.

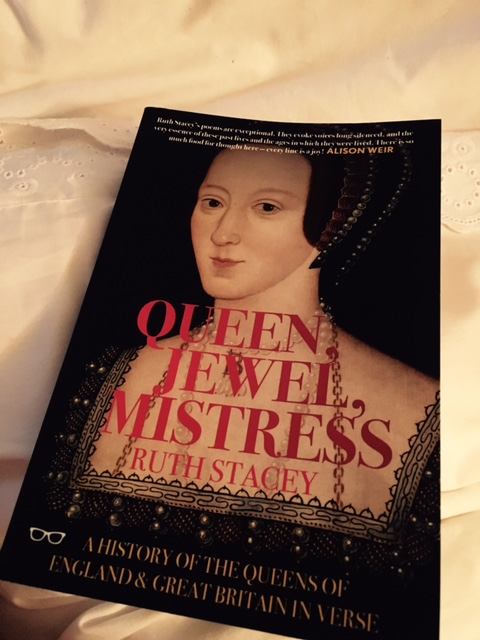

Ruth Stacey‘s collection Queen, Jewel, Mistress (Eyewear, 2015) vocalises the Queens of England and Britain, from the Anglo- Saxon era to the modern age: from Judith of Flanders (b. 844 AD) to Elizabeth II. A pretty impressive conceit. But how did the execution hold up?

First of all, I am staggered by the amount of research that has gone into this book. Staggered. A couple of pages at the back of the book indicate that lines from some of the poems are taken from letters, sermons, and poems written by the Queens themselves, as well as a number of books consulted in the course of Stacey’s research. Most helpful is the inclusion of brief biographies for each of the Queens, and the organisation of the book according to royal houses.

I don’t profess to know enough about the history of English Queens to assess the veracity of each poem, but I was interested in poems about Henry VIII’s wives and was struck by the deft handling of both historical and textual engagement. For instance, take the poem ‘Anne Boleyn’:

‘Deer do not tremble. I know this.

My bone and sinew twisted into fallow

slenderness and the tibia twig thin.

[…]

The poet’s words are wind-blown apples.’

The poet referenced here is likely Thomas Wyatt, a contemporary (and, according to some sources, lover) who compared Anne to a deer who could not be hunted because she belonged to the King. The poem ‘Catherine Howard ‘ imagines Henry VIII’s youngest wife addressing her lover, Thomas Culpeper:

‘Tom, will thou leave so soon? The door

is guarded against the slumbering King.

Who cares what the morn may bring?’

Each poem is marked by a different personality. I imagine it would have been easy to slip into a handful of voices, perpetuating these throughout the collection, but Stacey takes care to ensure that the character of each Queen is felt in each poem, at times funny, sad, formal, and yearning.

That these poems are grounded in historical fact makes for fascinating reading, but this is no mere history tour: Stacey is fascinated by the drama of these female lives, and captures them in verse via form, register and rhyme. This is what excites me most: she’s conscious of what poetry can bring to the reimagining of female history. ‘Elizabeth I’, for instance, incorporates a line from one of the Queen’s own verses, ‘for I am soft and made of melting snow.’ The use of rhyming couplets in the poem suggests the harmonising of Stacey’s poetic rendering with the Queen’s:

‘Robert Dudley calls me and I long to go,

For I am soft and made of melting snow.’

![FullSizeRender[1]](https://carolynjesscooke.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/FullSizeRender1.jpg)

The significance of this book as a work of art, however, is in its reclamation of history from the female perspective. That the poems themselves are brilliant, almost all of them adroitly executed, makes me want to stand up and give the book a round of applause. There is mastery here, boldness, and a lively assertion of what poetry can give to the historical imagination. This is a book that deserves widespread acclaim.

Both collections deserve to be frontrunners in the current poetic offering. To start with, I’m giving away both copies. Just say which collection you’d like in the comments box beneath this post, or on the Twitter/Facebook post linked to it, and I’ll draw names out of a hat on 14th Feb.